What makes one trumpet bell different from another?

Though certainly not the only factor, differences in trumpet bell shape, size, construction and material can greatly influence how a trumpet sounds and feels.

Here I’ll walk you through these differences and their implications for trumpet players. By the end, you’ll know how to compare bells, and importantly, understand the limitations of comparisons.

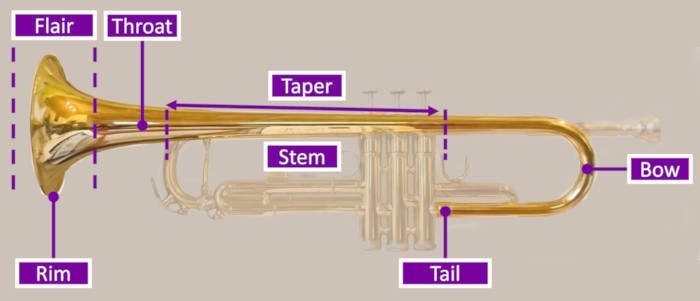

Parts of a trumpet bell

Even if you’ve been playing for some time, you may not know how to refer to each part of a trumpet bell. And though you may never need to know all these parts, knowing the main ones will help you make comparisons between bells.

Starting at the widest end of the bell the parts are as follows:

- Rim – also sometimes called the “bead”, though the bead also refers to the length of wire usually applied to the rim, and not all bells have beads.

- Flair – this is the part of the bell between the throat and rim where the bell curves outward.

- Throat – sometimes called the “transition”, the part where the flair joins the stem.

- Stem – the length of tubing extending from the throat to the curved bow.

- Taper – this refers to the particular shape of the stem, how quickly it widens, rather than an actual piece of the bell.

- Bow – sometimes called the “crook”, the curve in the bell’s tubing as it extends toward and then bends away from the player.

- Tail – the last length of tubing where the bell connects to the valve section of the trumpet.

For acoustical reasons, the brass on a bell is normally harder at the flare and softer at the throat with various degrees of hardness throughout the stem.

Trumpet bell construction

Trumpets can have either one-piece or two-piece bells. Let’s look at some of the main processes involved in making most trumpet bells.

One-piece bells

One-piece bells are normally built from a single sheet of material, usually brass. In the traditional hammering method, a craftsman follows these main steps:

- Tracing a shape into the sheet

- Cutting it out with sheers by hand

- Folding the shape in on itself

- Cutting notches into the outside edges

- Brazing the two edges together, forming a seam where the notches lock them in place

- Shaping the piece into a cone shape on a mandrel, typically by hammering it with a wooden or rawhide mallet

- Spinning the piece on a lathe and pressing a metal rod against the piece to form it into a flair shape

Throughout the hammering process, the craftsman repeatedly heats the piece with a torch to soften it and make it more malleable. Some trumpet players believe the tempering effect this annealing process has on the brass contributes to special tonal characteristics in the instrument.

Some have argued that seam placement can make a difference in how a trumpet sounds. While many manufacturers previously preferred to have the seam on the side so it’s less noticeable, some have chosen to move the seam to produce a certain sound.

One-piece bells can also be seamless. Some are made by extrusion, pressing the brass material through a die to the create the desired shape. Others are made by electroplating, applying metal to a bell-shaped mandrel and then removing the metal piece once it reaches the desired thickness.

Two-piece bells

Two-piece trumpet bells are the most common variety and most are built by brazing together a separate bell stem and flare.

Bell stems built for two-piece bells can be made either from sheet brass that is shaped into a tapered cylinder by hand or from brass tubing that is extruded on a tapered mandrel to form its shape.

In both cases the bells are then spun on a lathe to form their precise size, just as with one-piece bells. Though the craftsman usually needs to be extra careful when removing material at the seam where the bell flair joins the stem.

Gusseted two-piece bells are less common and are typically formed similarly to one-piece hammered bells. The main difference is that gusseted two-piece bells start out as two pieces of sheet brass, rather than one, and result in having two seams that converge along the bell stem.

Which bell design is best?

Traditional hammer-made one-piece bells tend to be more expensive than other varieties due to their high degree of labor intensity. But which trumpet bell design offers the best performance?

There’s much debate surrounding this question.

Some professional trumpet players have argued that one-piece bells offer more brilliance than their two-piece counterparts. They suggest two-piece bells are better suited for the cornet as a result.

Other musicians have claimed no consistent difference in sound between one- and two-piece bells. And then there are those who’ve claimed they’ve only noticed a small difference, and that ultimately bell choice is a matter of personal preference.

I tend to side with the latter judgment simply because the multitude of factors that can influence trumpet sound and tonality make it difficult to attribute specific differences to one bell type or another.

Differences in trumpet bell size

Trumpet players who compare bells tend to pay most attention to differences in size. Bell thickness, weight and diameter can all noticeably impact an instrument’s performance.

Bell thickness and weight

Bell thickness and weight are more or less the same dimension and can affect how a trumpet sounds.

A thicker bell will generally play more in tune and with better projection. A heavier bell will also produce a bigger, or fuller, and somewhat darker tone.

Thinner bells give the player more feedback and offer a more piercing quality but are less efficient and make maintaining proper intonation more challenging for the player. The main concern with these is that they’re more fragile.

Bell diameter

Most trumpets have a bell diameter under five inches, though a bell around 5.3-5.5 inches in diameter could offer wider projection. And I’ve heard of bells as large as six inches in diameter.

Smaller bells tend to have a more focused projection, rather than wider. They also speak with less effort and can therefore improve endurance. Though some players suggest smaller bells sacrifice some of the lower register.

Larger bells offer a wider, more even projection and are believed to help eliminate the shrillness common in trumpet projection patterns. Bells with a larger throat will also help give the instrument a darker tone.

Bell taper

The taper of a trumpet bell can also contribute how the instrument sounds. The bell taper describes how quickly the bell widens along the stem toward the throat.

Bells that taper faster, tend to produce a darker, mellower sound. Whereas bells that taper more gradually produce a brighter sound.

Bell material

The choice of bell material can certainly make a difference in how a trumpet sounds and plays.

But I’ll preface the below with the disclaimer that there are too many other factors that can make a difference—from the material hardness and annealing process, to the methods of the person spinning the bell to form the flair—for us to make consistently true statements about differences in materials.

Two manufacturers using the same brass material from the same supplier, for example, will not have precisely the same manufacturing process even between two trumpets of the same model in their respective facilities. And that’s to say nothing of all the other factors that affect trumpet playability and sound, such as mouthpiece, bore size and leadpipe.

This makes common comparisons, such as gold brass vs. yellow brass, practically moot.

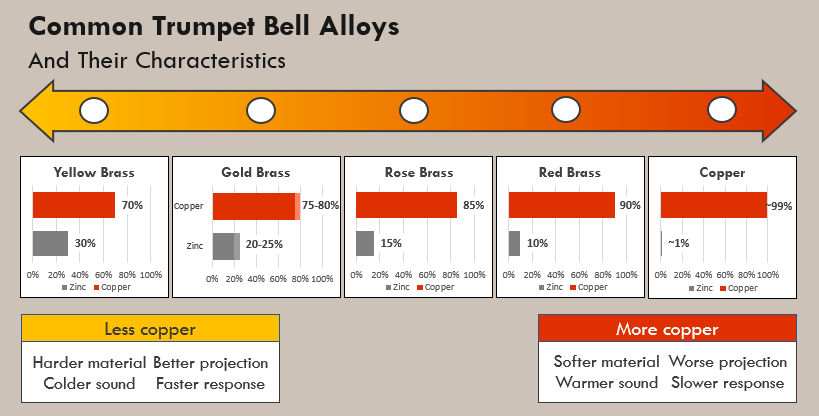

That said, brass, an alloy combining zinc with copper, is the most common material used for trumpet bells. Yellow brass, gold brass, red brass and copper, which in trumpet bells is nearly pure but still technically an alloy, contain varying amounts of copper.

The amount of copper is reflected in a few qualities in how the instrument plays and sounds.

Copper typically gives a warmer tone, while brass with more zinc creates a brighter, more sparkling tone. Some trumpet players also believe bells with more copper content offer a darker sound and better response. And copper is less vulnerable to corrosion.

But copper is a softer metal. And though copper is more efficient than brass, softer alloys don’t tend to project as well as harder ones.

Various types of bronze, an alloy usually made from copper, zinc and tin, are somewhat more common in bells made for high-end trumpets. Walter Lawson of Lawson Horns is believed to have first introduced Ambronze—a bronze with 85 percent copper, 13 percent zinc and 2 percent tin—to trumpet bells in the 1980s.

Apart from brass and bronze bells, nickel silver varieties are not uncommon. Nickel silver is an alloy of about 60 percent copper, 20 percent nickel and 20 percent zinc. Some players believe this alloy adds further edge and brightness to the trumpet’s sound.

Less common in bells due to its higher expense is sterling silver, an alloy much softer than brass and composed of 92.5 percent silver and 7.5 percent copper.

Conclusion

I hope you’ve found this brief tour of trumpet bells enlightening. The bell is just one feature of the trumpet that greatly influences how both players and listeners experience the instrument. Other parts of the instrument and the unique skill and anatomy of the player also determine the sound and feel of a trumpet.

For this reason, comparisons between trumpet bells can be challenging. But I encourage you to experiment with different bells and different trumpet models. You’re bound to appreciate unique characteristics in each.

Leave a Reply