Are you using the right trumpet mouthpiece for you?

As the connection between you and your instrument, no other accessory has a greater impact on playing the trumpet than the mouthpiece. That’s why it’s so important to ask yourself regularly: am I playing with the right mouthpiece?

But answering this question isn’t easy. And no one can answer it for you because there are so many factors that go into determining which mouthpiece is best.

Here I’ll explain trumpet mouthpiece sizes, shapes and features and how they affect playing, as well as strategies to help you choose a mouthpiece.

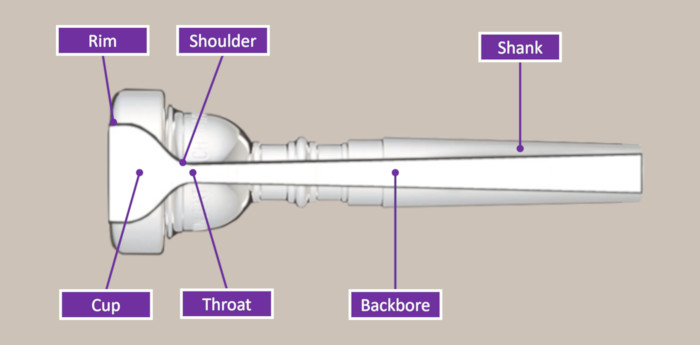

Parts of a trumpet mouthpiece

Before we get into interpreting mouthpiece sizes and how to choose the best one for you, an understanding of the different parts and their effects on sound, comfort and playability is essential.

Note that although each part of the mouthpiece affects play in different ways, how a player experiences their instrument will be a function of how ALL parts of their mouthpiece work together.

Moreover, a player’s own ability, such a their embouchure strength, and their physiology, such as lip size, will also factor into how they sound and feel using a particular mouthpiece.

Rim

The rim is the top edge of the trumpet mouthpiece and has implications for a player’s tonal range, comfort and endurance. Thickness and bite are the main characteristics that affect these aspects of mouthpiece playability.

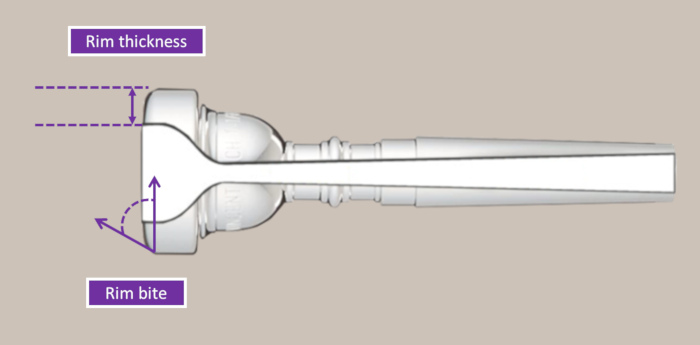

Rim thickness or width

Mouthpiece rim thickness can affect playing comfort, tone articulation and endurance.

A thinner rim means less contact with the lips, and therefore more lip vibration and tonal flexibility and range. At the same time, a narrower rim tends to “cut”, or press, into the lips, which can hinder blood circulation, thus limiting a musician’s ability to play continuously for a longer duration.

A wider rim offers more comfort and better endurance, since it diffuses the pressure applied to the lips over a wider contact area.

As a general rule, thinner rims are better suited for trumpet players with thicker lips, while wider rims are better suited for trumpet players with thinner lips.

Rim bite

Rim bite affects play similar to how rim thickness affects it. Bite is the term we use to describe the inside corner of the rim between the top edge of the rim and the inside wall of the cup.

A sharper rim bite, like a thinner rim, is typically better for players that have thicker lips because it helps to hold the fleshier lips back from sliding into the cup. This allows for faster vibration and response. Without this sharper rim, a thicker-lipped player is more likely to use excessive pressure to again their mouthpiece.

Thin-lipped players normally can’t tolerate mouthpieces with a sharper bite due to the problems with blood circulation and irritation that often result. Although a bite that’s too rounded offers too little control and response, a rim bite on the more rounded side is generally going to be the best choice for a player with thin lips.

Cup

The cup of a mouthpiece is the large open space within the top.

As the space where the lips are meant to vibrate, the cup is also the most critical feature of the mouthpiece. And trumpet players often spend years searching for the mouthpiece with the cup that most closely complements their playing style, ability and physiology.

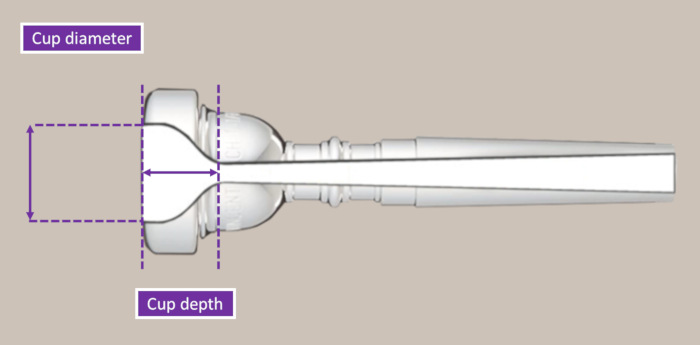

Cup diameter

As one of the only measurements explicitly included in most model numbers, cup diameter is a basic and defining feature of mouthpieces. Sometimes referred to as the rim diameter or inner diameter, cup diameter is the length from one side of the inside rim to the opposite side.

The wider the cup diameter, the more the player’s lips are allowed to freely vibrate within the mouthpiece.

Musicians often attribute clearer tone, at the cost of more effort, to wider mouthpieces. Because wider mouthpieces allow for more lip inside to create more vibration, more mouth muscles are needed to engage the lips, which requires more effort.

Some have suggested they get more volume with a wider mouthpiece, while others suggest that playing a mouthpiece with a smaller diameter makes playing high notes easier.

Despite cup diameter being a critical factor in choosing the right mouthpiece, measuring it can be tricky. Different companies measure the diameter at different depths in the mouthpiece.

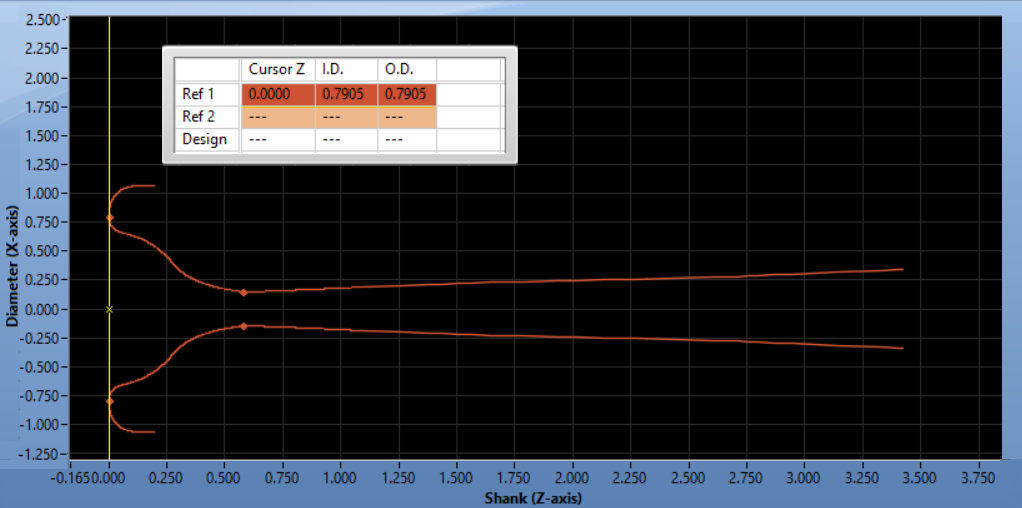

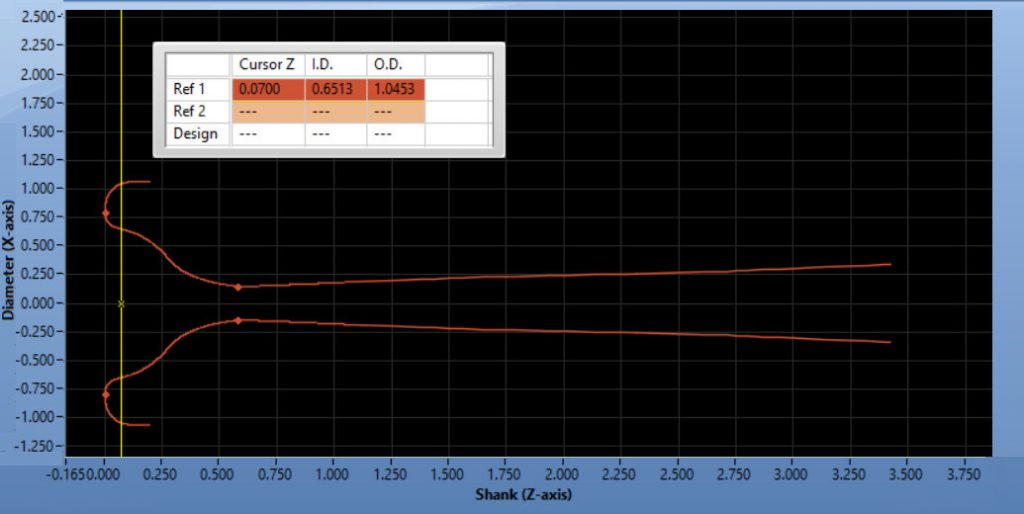

For example, the image below shows the profile of a Bach 5C mouthpiece using VennCAD software. You can see the software reports the point I’ve chosen to measure as having a diameter of 0.7905 inches.

But if I choose a deeper point on the cup to measure diameter, I get a smaller figure, 0.6513 inches.

Bach measures their mouthpiece diameters one way, Schilke measures theirs another way and Yamaha measures theirs still another way. That’s why popular mouthpiece comparison charts can be more confusing than helpful. So be careful putting too much faith in cup diameter figures without understanding how they’re being measured and reported.

Cup depth

Cup depth is a second measurement of cup volume from the top opening to the throat where air is funneled into the backbore.

A brighter sound and more endurance in the higher register is often attributed to smaller cups. This doesn’t necessarily mean a smaller cup will make it easier to hit higher notes, but it may make it easier to play these notes for longer.

Mouthpieces with a deeper cup tend to offer a darker tone. Due to these differences, many trumpet players believe mouthpieces with larger cups are better suited for jazz musicians and those with smaller cups are better for orchestra musicians.

Cup shape

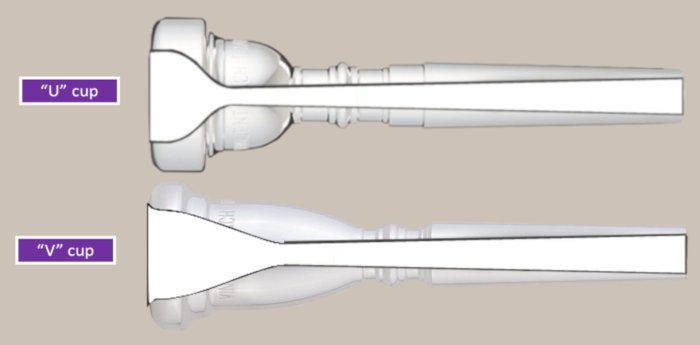

Besides size, cup shape is another feature that will impact playing. Trumpet mouthpieces come in two basic shapes: a “U” shape that tapers more gradually from the rim down to the throat and a “V” shape that tapers more sharply.

Comparing how water drains in two differently shaped sinks can help you understand the difference cup shape can make. Water tends to pool in the bottom of a flatter sink before draining slowly. Whereas a sink that tapers more sharply acts more like a funnel, draining water more quickly.

Similar to water in a sink, air moves more quickly through a mouthpiece with a cup that has a “V” shape, which tends to brighten the sound from the trumpet. And air moves more slowly through a mouthpiece with a cup that has a “U” shape, which tends to darken the sound.

Most mouthpieces are designed to strike some kind of balance between the two shapes to allow for more versatility.

Shoulder

The shoulder is the part of the cup near the bottom where it curves inward to funnel air into the throat. This isn’t one of parts that most trumpet players obsess about. But as the first area of resistance for air moving through the mouthpiece, the shape of the shoulder can affect how the instrument sounds.

You may notice less air resistance and a darker tone with a smoother, flatter shoulder. While you’re more likely to experience more air resistance and a brighter tone with a shoulder that slopes more sharply inward.

Throat

The hole bored into the bottom of the cup that joins it with the backbore is what’s called the throat. A larger throat size lets you play with greater volume. But because the larger hole allows more air to pass through at once, larger throats also offer less endurance than smaller ones.

Bigger mouthpiece throats will also make the softer dynamics a little bit more velvety and transparent sounding compared to a smaller-throat mouthpiece… In my experience, the most dramatic effect of increasing the throat size is that the sizzle point, or that point when the sound becomes zingy and brilliant, is at a louder dynamic than when you use a smaller mouthpiece throat.

Jon Kaplan, Jon Talks Trumpet

Modifying the throat

Some trumpet players may be tempted to bore out the throat of a mouthpiece they own to try to capture some of the benefits of a larger throat size. But although this is the most common and inexpensive mouthpiece modification, doing so often comes with collateral damage to the mouthpiece that often offsets the desired effects.

For one, drilling into the throat will lengthen the shoulder, which will increase resistance. Changing the throat this way also often alters the taper of the backbore, which will affect how the mouthpiece plays.

Backbore

Once air travels through the throat, it enters the backbore, a long, tunnel-like path extending to the bottom end of the mouthpiece. When we talk about differences in backbore we’re really talking about its taper and size.

A tighter, or smaller, backbore tapers more rapidly and offers more control, often helping in the upper register, but also gives more resistance. A larger backbore generally produces a darker sound with less resistance. Too little resistance can make intonation less stable and the upper register sharper.

Shank

The shank is the name for the long tube of the mouthpiece that fits into the receiver of the instrument.

The most important feature of the shank is just that it must fit firmly. The outer diameter of the shank will determine how deeply it fits in the receiver, and therefore, has implications for trumpet pitch and playing comfort.

Trumpet mouthpiece size numbering systems

One of the most frustrating aspects of mouthpieces is their confusing naming conventions. Models are usually named according to their size. But different manufacturers have adopted different systems over the years.

We’ll cover a few of the main brands here.

Bach mouthpieces

Bach uses numbers and letters to represent size in naming their mouthpieces. In the Bach 7C mouthpiece the “7” refers to the rim diameter, or inner diameter, and the “C” refers to the cup depth, or cup volume. Lower numbers and earlier letters in the alphabet represent larger sizes.

In general, a Bach mouthpiece with a “1” in the name has a wider diameter than one with a “2”, which has a wider diameter than one with a “3” and so on. And a Bach mouthpiece with an “A” in the name has a larger cup than one with a “B”, which has a larger cup than one with a “C”, etc.

But there are inconsistencies within this naming system. Some 5Bs have a wider inner diameter than some 5Cs, for instance.

What’s more, not every Bach mouthpiece model name contains exactly one number and one letter—some have more. The 1CW model is the same as the 1C but with a wider cushion rim denoted by the added “W”. Other models are named with a single number and no letters—like the 2 and the 8 1/2.

Schilke mouthpieces

In contrast to the Bach system, Schilke mouthpieces use numbers to denote size in the opposite order—so smaller numbers stand for smaller mouthpieces.

Schilke also uses one additional number (1-5 from roundest to flattest) referring to the rim contour, and one additional letter referring to the backbore taper as follows:

- a = Tight

- b = Semi-tight

- c = Standard

- d = Medium large

- x = Large; for piccolo trumpet

- z = Extra-tight

Schilke’s Standard Series 12B4 mouthpiece, for example, has a “B” cup on the medium-small end and a semi-flat rim.

And similar to the Bach naming system, some Schilke model names sometimes omit the first letter for cup size, the second number for rim contour or the second letter for backbore when these features are standard (“C” cup size, “3” rim contour and “c” backbore are standard).

So the Standard Series 9 mouthpiece would be written as “9C3c” if it wasn’t redundant to mention the standard cup, rim and backbore.

At minimum, every model name includes the first number for inner diameter. And whenever the rim contour is NOT standard, you will see the first letter included with the second number for rim contour, even if that model’s cup is a standard “C” cup, as with the 9C4 model.

Yamaha mouthpieces

Yamaha also uses up to two numbers and two letters in their mouthpiece model numbering but with a couple differences from Schilke:

Yamaha uses a number range of 5-68 (narrow to broad) to represent inner diameter and the letters “a”, “b”, “c”, “d” and “e” to represent backbore taper (“narrow” to “broad”, which we can consider similar to Schilke’s “tight” to “extra-tight”).

Yamaha trumpet mouthpiece names are also typically written with the letters “TR” up front, such as TR-6A4a, to distinguish them from those built for cornets, flugelhorns and other types of instruments.

How to choose a trumpet mouthpiece

Finding the right mouthpiece isn’t easy. For one thing, everyone is different. Some people have a dental structure that makes one mouthpiece more comfortable than another. Others have certain musical strengths as a trumpet player that certain mouthpieces accentuate.

Start by considering your lips

I’d say the most important factor, and a good starting point for choosing a mouthpiece, is lip structure. Knowing whether you have thinner or thicker lips, as well as the shape of your top lip relative to your bottom lip, will help determine what rim thickness and bite are ideal for you.

From here, I’d suggest trying out different brands to see whether one stands out as more comfortable than others.

There’s a wide variety of rims out there, and most manufacturers have more than one. But there’s usually some sort of family resemblance. So if you find a rim that’s comfortable, then maybe confine your search, at least at first, to that manufacturer.

If you’re still not sure whether a particular mouthpiece is the right design for your lips, you might try the lip stick test to look for lip intrusion (I’m not kidding).

Some manufacturers can custom build a mouthpiece that’s fitted to your specific mouth structure. These fitted mouthpieces tend to be much more expensive than mass-produced models. But if you play often enough, they may be a worthy investment.

Trying out mouthpieces

Try some mouthpieces based on your lips with the aim of finding something comfortable. Then I’d recommend spending at least a couple weeks playing with it regularly before you give up on it. Becoming accustomed to a particular mouthpiece doesn’t happen overnight.

Ask an experienced friend or trumpet teacher to listen to you play from a distance. Try playing with both your main mouthpiece and a new one and then ask for feedback. Musicians tend to feel and hear their instrument differently from how an audience tends to perceive it. So it helps to get a second or third opinion based on how a mouthpiece suits you.

Decisions based on playing style

As I’ve mentioned throughout describing the different mouthpiece parts, some shapes and dimensions tend to lend themselves better to particular musical styles.

For example, larger mouthpieces are generally more popular with orchestral players. And smaller mouthpieces are more popular with lead or commercial players.

But there are exceptions to these rules. And many trumpet players own multiple mouthpieces suited for different playing styles. So you can consider playing style in your choice of mouthpiece, but don’t let it hold you back from experimenting.

Common mistakes with choosing a mouthpiece

Although the lack of strict rules for choosing a mouthpiece can make the process difficult, avoiding some common mistakes can save you some time and money.

1. Emulating other players’ mouthpiece preference

Some trumpet players choose a mouthpiece based on what their teacher uses. Others love the sound of a famous trumpeter, like Miles Davis, and think getting the same mouthpiece he used will help them sound more like him.

Mouthpieces are a preference. And as we’ve seen, there are just too many other factors that influence playability and sound to suggest that one mouthpiece will make you sound like someone else. So look for one that’s best for you.

2. Applying general rules about mouthpiece fit too rigidly

The general rules we’ve discussed here are helpful guidelines. But they’re by no means the final say in what mouthpiece you should play with. Just because you have one type of anatomy, for example, doesn’t mean certain mouthpieces are off limits to you.

There are inherent qualities in the cup size that help you play “big” and inherent qualities in compression that help you play “high”. But everybody is different physically, and this has more to do with it. My friend, Don Clarke, uses a tiny mouthpiece and gets a huge sound, and he’s got a big old melon of a head (sorry, Don!) and massive lips. Byron Stripling is physically the same as Don, but uses a much bigger mouthpiece – equally big sound.

Willie Murillo, Woodwind & Brasswind

3. Giving up on a mouthpiece too early

Many trumpet players get caught up in trying lots of different mouthpieces in rapid succession, what some players call a “mouthpiece safari”. This is a mistake.

To be sure, you can often discover a mouthpiece doesn’t feel comfortable as soon as you try it out. And you’d be right to move on to another mouthpiece when this is clear to you.

But getting acclimated to a mouthpiece to the point you can truly know what it will do for your playing is going to take time. So take at least 2-3 weeks to get adjusted to the feel and play of a particular mouthpiece before you decide whether it’s right for you.

Conclusion

Trumpet mouthpieces are a complex subject. But if you’ve made it this far in reading about them, you’re on solid footing to start hunting for one that complements you well.

Finding the right mouthpiece is a journey that will likely continue for as long as you play the trumpet. As your abilities change, so will your strengths and weaknesses. The muscles around your mouth will develop differently. And your tastes in terms of music style will likely change as well.

So be sure to try a new mouthpiece every once in a while, even if you’re happy with the one(s) you have. It might just take your playing to a new level.

Have you found the right mouthpiece for you? Tell us about your experience in the comments section below!

Great article! I’m 74. I’ve played on a Schilke 18 since college. I was a lead in Navy Bands before college.

I agree about sticking with a mouthpiece long enough to truly know if it works for the player. Too many younger players seem to use multiple mouthpieces. I was taught a very long time ago this was a bad practice, especially for developing players.

Hey Michael, thanks for your comment. Too true!

How about asymmetrical mouthpieces? Should everyone try them? I own a wedge mouthpiece.

Hi David,

I haven’t personally tried a wedge mouthpiece, but some trumpet players attest to getting a wider range and even tone across registers with one. Given the variability in experience with mouthpieces from one player to the next, I’d be inclined to suggest interested players give asymmetrical mouthpieces a try. But as this author has made clear, always give a mouthpiece adequate time before giving up on it.

Chosing the correct mouthpiece is difficult for all trumpet players, I understand. I just had a full upper dental arch implant installed. Retraining is very difficult. My dentist said my embouchure will remember. Bullshit. How do you help someone choose a mouthpiece when you go from an imperfect embouchure to a perfectly symmetrical embouchure? The mouthpiece doesn’t stay in one place. Endurance sux, intonation ain’t great but getting better, range is in the tank. Help! I need advice from someone that knows more about my embouchure better than me.